The Bookshelf That Wobbles, Yet Stays

I’ve lost months of my life to books I didn’t even enjoy. Entire winters, locked in a slow duel with a badly written novel, just because I’d already invested the first hundred pages. Somewhere along the way, the act of finishing became a moral duty.

Psychologists call this the IKEA effect: our tendency to overvalue anything we’ve put effort into. The bookshelf you assembled yourself, even if it wobbles every time someone sneezes, feels superior to the perfectly aligned one you bought ready-made. Extend that logic and you’ll understand why people cling to doomed startups, defend failing relationships, and keep re-electing the same disappointing politicians.

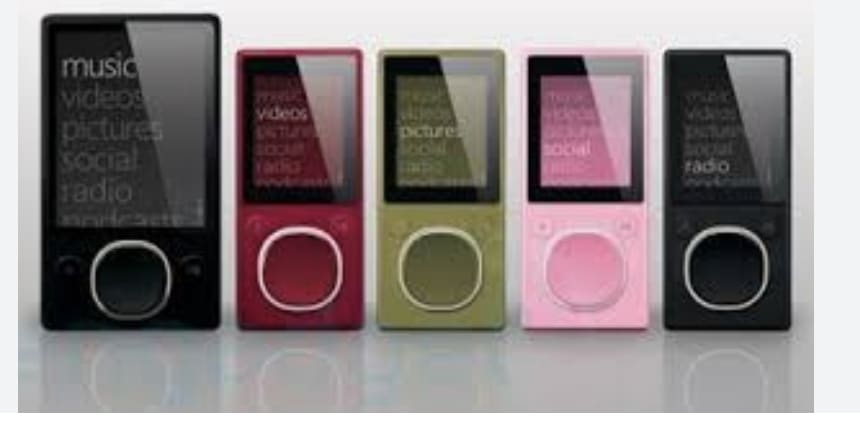

From Zune to Zeher 2

Think of Microsoft Zune. It was meant to kill the iPod. Instead, it died an embarrassing death, but not before millions were spent on marketing, partnerships, and development. Or take the graveyard of flashy Indian startups that raised millions only to shut shop within a year, ones that promised everything from drone deliveries of biryani to “the Netflix of tuitions.”

Bollywood, never one to be left behind, has its own IKEA effect showroom. Housefull 5, Race 3, Student of the Year 2, Dhoom 3. Sequels nobody asked for, funded on the belief that since we’d tolerated the franchise this long, we might as well see it through. It’s less about story and more about sunk cost.

The Neuroscience of Stubbornness

Why do we do this? Neuroscience has answers.

Dopamine: Every ounce of effort tricks the brain into releasing dopamine, giving us the illusion of progress.

The Prefrontal Cortex: It whispers that persistence is noble, even when persistence is just well-packaged denial.

The Striatum: This part of the brain values consistency so much that abandoning a bad idea feels like abandoning yourself. If you’ve been saying for years that your project, partner, or politician is the future, walking away feels like admitting your identity was built on a lie.

This is why you still defend that friend who never remembers your birthday. Or why people still stand in line at rallies for leaders who’ve failed them repeatedly.

Bad Books, Bad Relationships, Bad Votes

The IKEA effect doesn’t just belong to economists or psychologists. It lives in our living rooms and our WhatsApp chats.

Books: You finish the dreadful novel because you’ve already slogged through 300 pages. The idea of abandoning it feels like betraying the hours you’ve already lost.

Relationships: That relationship where you keep insisting “he’ll change,” even though he has the emotional range of a teaspoon.

Politics: You vote for the same disappointing leader because change feels like chaos. Better the devil you know, right?

In each case, effort masquerades as evidence of value.

The Personal IKEA Showroom

I see it in my own life.

The candle-making hobby to my love for art. I have more watercolour than most professional artists.

The running shoes in 4 colours that sit in the corner, proof that buying equipment is not the same as building endurance.

The half-written novel I drag from laptop to laptop, even though I secretly know it reads like a very long LinkedIn post.

Every one of them is a crooked bookshelf I can’t bring myself to throw away.

The Bollywood Sequel in Our Heads

We like to believe life is about decisive, glamorous turning points – quitting jobs, moving cities, breaking up dramatically. But in reality, our lives are shaped more by the quiet accumulation of these crooked bookshelves, these sequels we never stopped buying tickets for.

That’s the real punch of the IKEA effect: it doesn’t just make us cling to the past; it makes us imagine a future built on it. If I’ve already lived with the bad sofa for five years, surely it will become comfortable by year six. If I’ve already endured Student of the Year 2, surely 3 will redeem the franchise.

How to Walk Away Without Regret

The way out, psychologists say, is to think in terms of regret minimization. Imagine yourself at 80. What will sting more: abandoning the half-built bookshelf or wasting decades trying to convince yourself it was straight?

Jeff Bezos used this logic to quit his Wall Street job and start Amazon. You can use it to abandon a bad novel, an unworkable idea, or a politician who has “been learning on the job” for decades.

Walking away isn’t cowardice. Sometimes it’s the most precise form of honesty available.

I can’t do this anymore

The IKEA effect reveals something uncomfortable about us: that we confuse investment with worth. We mistake persistence for virtue. But not everything we build deserves to last. Some books should be put down. Some leaders should be voted out. Some sequels should never be funded.

The trick isn’t to stop building – it’s to know when to walk away from the bookshelf that will always wobble.